A little overview about terminals

As a developer, you must have gotten your hands dirty with terminal emulators at some point in your career. They are powerful tools that allow you to interact with your operating system and run commands from the command line. You might think that it is just text in a black box, but it’s much more than that.

You see, in the early days of computing, a computer was literally a green/white text on a black background. This you can say is a true computer, you give some input, and you get some output. But as time went on, we moved on from that and started using graphical user interfaces (GUIs). GUIs allowed us to interact with our computers using a mouse and a keyboard, but they were not as powerful as terminal emulators. Behind the scenes, a GUI is just executing commands that we used to enter manually in the terminal.

In the UNIX world, the approach was to let the operating system kernel handle all the low-level details, such as word length, baud rate, flow control, parity, control codes for rudimentary line editing and so on. Fancy cursor movements, color output and other advanced features made possible in the late 1970s by solid state video terminals such as the VT-100, were left to the applications. We will come back to this VT-100 protocol later.

Getting a bit technical

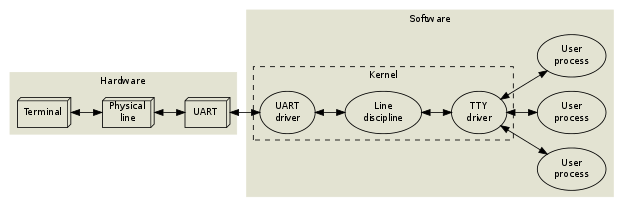

A terminal emulator works via connecting to a TTY. TTY stands for Teletype Terminal, which was a device used for communication between computers in the early days of computing. It was a simple device that allowed users to send and receive text over a serial connection.

TTYs were used to connect computers to mainframes and other remote systems. They were also used to connect terminals to each other, allowing users to share resources and collaborate on projects. TTYs were a key component of the early days of computing, and their influence can still be seen in modern terminal emulators. A user types at a terminal (a physical teletype). This terminal is connected through a pair of wires to a UART (Universal Asynchronous Receiver and Transmitter) on the computer. The operating system contains a UART driver which manages the physical transmission of bytes, including parity checks and flow control. In a naïve system, the UART driver would then deliver the incoming bytes directly to some application process. But such an approach is quite primitive, and quite lacking by today’s standards.

Of course, TTY’s etymology has a long history that has evolved and became more flexible in terms of how it is implemented and works

In modern linux kernels, TTY live under /dev/pts. This directory contains virtual TTY that exist only in memory. The TTY files located in /dev that have names like /dev/ttyS0 or /dev/ttyUSB0 are connected to physical serial ports on the computer (like arduino).

$ ls -ll /dev/pts/

total 0

crw--w---- 1 funinkina tty 136, 0 Mar 4 11:17 0

crw--w---- 1 funinkina tty 136, 1 Mar 4 11:02 1

crw--w---- 1 funinkina tty 136, 2 Mar 4 11:18 2

c--------- 1 root root 5, 2 Mar 4 10:48 ptmx

In most unix systems, the ptmx is a master and all is started by the system. The rest of tty are slave of the ptmx. The kernel keeps track of what processes are controls the master for each slave device.

Here we can see that there are 3 TTY present. In most linux distros, the display manager (the screen from which you log in) runs on TTY-1 and after logging in the desktop session is started on TTY2. You can check which TTY you are currently in by:

$ loginctl session-status

3 - funinkina (1000)

Since: Tue 2025-03-04 10:49:14 IST; 40min ago

State: active

Leader: 1270 (gdm-session-wor)

Seat: seat0; vc2

TTY: tty2

Remote: no

Service: gdm-password

Type: wayland

Class: user

Idle: no

Unit: session-3.scope

├─1270 "gdm-session-worker [pam/gdm-password]"

├─1319 /usr/lib/gdm-wayland-session /usr/bin/gnome-session

└─1324 /usr/lib/gnome-session-binary

Mar 04 10:49:15 archlinux systemd[1]: Started Session 3 of User funinkina.

Before this post becomes entirely about TTY and linux, let’s go a bit further into terminal emulators.

Communication in Terminal Emulators

You can think of a terminal emulator as a web browser, but it renders using VT-100 protocol unlike HTML. Like how a browser sends requests to a web server, the terminal sends data to your shell (bash, fish or zsh), and instead of using internet, it uses a TTY to communicate.

Every UNIX-like app (including Linux apps) are provided 3 channels by the operating system, the “standard input” (a.k.a. stdin, file descriptor 0) which is used to feed bytes into the program, the “standard output” (a.k.a stdout, file descriptor 1), which is used to feed bytes out of the program, and the “standard error” (a.k.a. stderr is file descriptor 2), which is a channel that can report problems during computation without disrupting the “standard output”.

Your command line shell program, usually bash, is just an ordinary program. Like all other programs, when you launch Bash the OS gives it a stdin, stdout, and stderr channels of communication. Often times you can feed input from a text file directly to Bash’s stdin channel and it will behave as though a user typed every single character in that file – with a few caveats, Bash can detect when it is receiving genuine user input or input from a text file and behaves slightly differently in each case.

Launching the terminal

Whenever you launch a terminal (gnome-terminal, konsole, kitty), it connects to the master tty - ptmx and starts a subprocess. This subprocess can be seen as a synonym to virtual tty. It is this subprocess in which your shell will be running in, by default it’s most probably bash or zsh.

Modern Unix systems don’t use physical TTYs (like /dev/ttyS0 for serial ports) for terminal emulators; they use pseudo-terminals (PTYs). A PTY is a pair of virtual devices: a master and a slave. Here’s how it’s allocated:

- The terminal emulator calls a system function like

open("/dev/ptmx")to request a PTY master device from the kernel./dev/ptmxis the “pseudo-terminal multiplexer,” a special file that manages PTY allocation. The kernel assigns an unused PTY pair:- Master side (e.g.,

/dev/pts/ptmx): This is the emulator’s end, where it sends output to be displayed and receives input from the user. - Slave side (e.g.,

/dev/pts/0): This is the TTY that the shell or program will use as its controlling terminal.

- Master side (e.g.,

The emulator opens the master side, and the kernel creates a corresponding slave device file (e.g., /dev/pts/0), which is numbered sequentially based on availability.

The terminal emulator needs to prepare the slave side (the TTY) for use by a program like a shell:

- It uses

grantpt()andunlockpt()system calls to set permissions and unlock the slave device, ensuring the process running inside can access it. The emulator retrieves the slave device’s name (e.g.,/dev/pts/0) with a call likeptsname().

Now the TTY needs a shell to interact with the user and system. It doesn’t inherently know which shell to start, as different users might use different shells. The default shell for each user is stored in the /etc/passwd file. This file serves as a primary database for user account information on posix systems. Each line in this file represents a user and follows this format:

username:password:UID:GID:GECOS:home_directory:shell

The shell field contains the path to the user’s default shell (like /bin/bash or /bin/zsh). The terminal emulator reads this field and starts the shell in the TTY.

You can check your default shell by:

$ echo $SHELL

/bin/zsh

-

To start the user’s shell inside the PTY, the terminal emulator uses the

fork()system call to create a child process.Thefork()ensures that the parent process, i.e. the emulator keeps control of the PTY master. The child process then callssetsid()to create a new session and process group, detaching itself from the terminal emulator. This is necessary to prevent the shell from receiving signals intended for the emulator. -

setsid()opens the slave device (e.g.,/dev/pts/0) and assigns it to stdin, stdout, and stderr usingdup2()or similar calls. This makes the PTY slave the controlling TTY for the session. Now it needs to know which shell to start. The shell is started by callingexecvp()with the path to the shell binary (e.g., /bin/bash) as the first argument. This replaces the child process with the shell process, which inherits the PTY slave as its controlling terminal. -

The child process gets the shell’s login shell from the user’s

/etc/passwdentry and starts it. The shell reads its configuration files (like~/.bashrcor~/.zshrc) and presents the user with a prompt. The user can now interact with the shell, which sends input and output through the PTY slave to the terminal emulator. -

The

execvp()command that executes the shell replaces the child process with the shell process. This is why when you exit the shell, you return to the terminal emulator. The shell process is the only one running in the PTY slave, so when it exits, the PTY is closed, and the terminal emulator displays a message like “Process completed”.

So in a nutshell, the terminal forks a tty from master tty, reads the user’s default shell, reads that shell’s default configuration files and starts the shell in the tty. The shell then reads the user’s configuration files (.bashrc or .zshrc in user’s home directory) and presents the user with a prompt. The shell reads the prompt style or any initial style from the configuration files and displays through stdout() to the terminal emulator. This stdout() is called over the PTY. The user can now interact with the shell, which sends input and output through the PTY slave to the terminal emulator. We will see how the terminal emulator renders the prompt and text in the next section.

Now you are ready to type in the terminal and execute commands. But how does the terminal emulator know what you are typing? Let’s find out.

Typing in the Terminal

To execute anything in the terminal, you obviously need to type the command, but typing in a terminal is not like typing in any text editor. Each character you press is sent to the shell as a byte, and the shell by default echoes it back on the screen. If you execute stty -echo you won’t see anything you type being echoed back. This is how password prompts work. But pressing enter will still execute the command. You can re-enable echo by stty echo.

But we are humans after all, and humans make mistakes and so arise the need of clearing the echoed characters, going back and forth in the line, etc. Therefore the operating system provides an editing buffer and some rudimentary editing commands (backspace, erase word, clear line, reprint), which are enabled by default inside the line discipline. The line discipline is a part of the kernel that processes input from the terminal and provides some basic editing capabilities. The line discipline is responsible for handling the input from the terminal, processing it, and passing it on to the shell. Some advanced terminal applications like neovim, btop use their own line discipline, like curses, ncurses or readline. This is also known as running in raw mode and handle all the line editing commands themselves. The line discipline also contains options for character echoing and automatic conversion between carriage returns and linefeeds. Think of it as a primitive kernel-level sed , if you like.

Whatever the user types in text is buffered in the PTY’s stdin line buffer. The shell then echoes back the character using stdout() and the terminal emulator renders it on the screen.

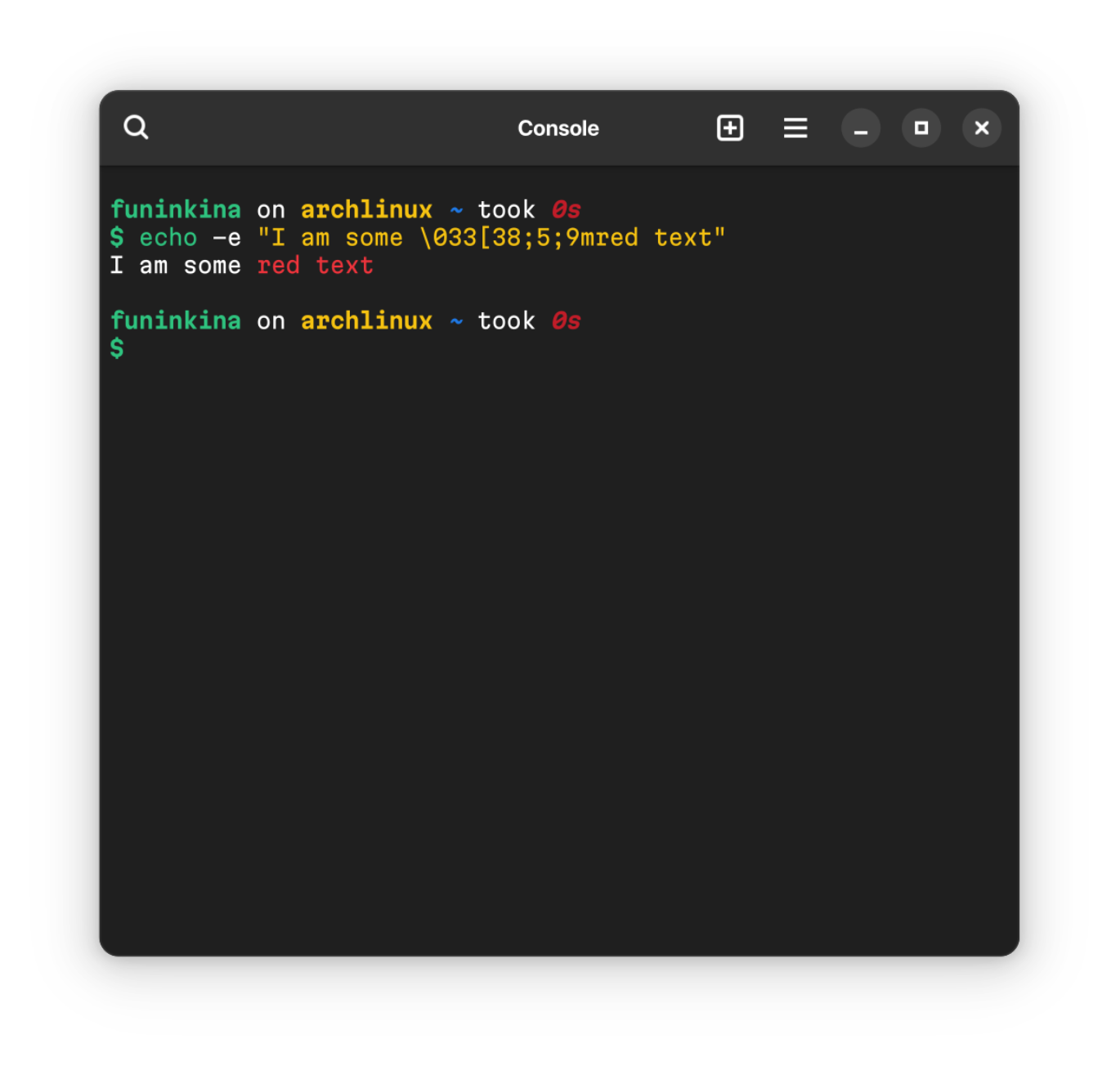

Whenever the shell sends data to the terminal emulator, it uses ANSI escape codes. These codes are a standard for controlling text formatting, color, and cursor movement on terminals. They are used to move the cursor around the screen, change text colors, and clear the screen. The terminal emulator interprets these codes and renders the text on the screen accordingly. The shell sends the text to the terminal emulator over the PTY, and the emulator displays it using the VT-100 protocol. The VT-100 protocol is a standard for controlling text terminals and is used by most terminal emulators today.

You can see the entire list of ANSI escape codes here .

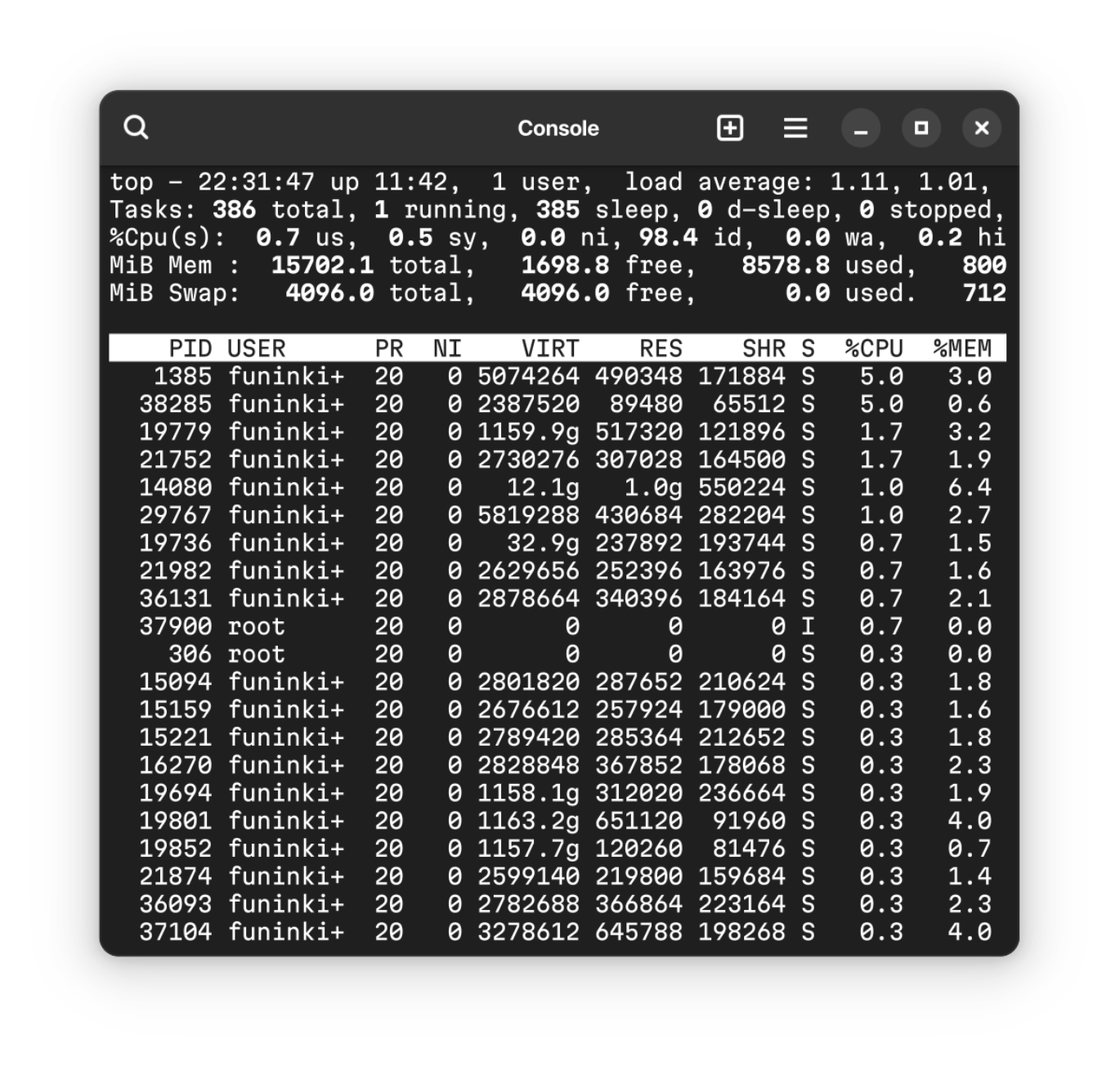

Using all these codes, you can have anything from a simple text based output to full on text editors like vim, neovim and even system monitors with progress bars, graphs and more (like top, btop).

Closing and References

When you type a command in the terminal and press enter, the shell reads the command and executes it. This process is very extensive in its own, and I will cover it soon in a separate post.

I hope this post gave you a good understanding of how terminal emulators work under the hood.